Freeport, ME, June 22, 2021

Documenting a Disappearing Maine

Former L.L.Bean Stylist Basha Burwell and her collaborators preserve the Pine Tree State aesthetic in new photo book

WORDS BY JAY MOYE, PHOTOS BY MAURA MCEVOY

As a freelance prop stylist, Basha Burwell spent more than 15 years recreating the Maine look on L.L.Bean catalog shoots around the world.

“I was the resident Maine authenticator,” Burwell recalls. “I loved it… it didn’t really seem like a job because it's simply who I am.”

The third-generation Mainer provided photo crews with on-set guidance for how New England outdoor scenes should feel—from the clothes to the gear to the décor.

“We always shot out of season, so we’d be in Sonoma for fall and Sun Valley for winter,” said Burwell, an avid Nordic skier and sailor. “I was the one to ask if the skis were on right, or if the boat was tied correctly to the dock. I worked with some amazingly talented photo crews, but not many lived the Maine lifestyle, so they didn’t know the first thing about how a toboggan should be tied or how snowshoes should fit.”

Today, Burwell—who divides her time as an art director and jewelry designer—continues to cherish her role as ambassador of the Pine Tree State aesthetic. This month, she and photographer Maura McEvoy and journalist Kathleen Hackett will publish The Maine House, a book of photos and essays capturing what famed local artist Jamie Wyeth called Maine’s “singular and unique” quality of life.

Burwell on Location with L.L.Bean, carrying prop dog.

Holiday shoot, Sun Valley. Photo Credit: Augustus Butera

Burwell and McEvoy saw their beloved state evolving and felt a pull to preserve its living history. “We set out to document a disappearing Maine,” said Burwell, 52. “We started by saying, ‘Let’s shoot properties we feel something strongly about and go from there’.”

First up was author E.B. White’s former home in Brooklin on Blue Hill Peninsula, not far from where Burwell lives with her family. She’d visited the farm before, touring the writing shack where White penned Charlotte’s Web and other classics, and making cider with apples that had fallen to the ground. New owners were set to close on the estate, leaving a short window before it changed hands.

The autumn shoot was a success, inspiring them to scout additional homes. “It became clear to both of us that we wanted to capture a Maine we felt was changing very quickly,” Burwell said. “We were drawn to soulful, lived-in, well-loved homes—not designer houses with hired decorators. We wanted to preserve these beautiful, multi-generational spaces where families’ lives and histories came through.”

Over the course of four years, Burwell and McEvoy scoured the state for subject matter—guided not by maps or GPS devices, but by their creative instincts and shared love of Maine’s fading yesteryear. Chasing tips and invitations from acquaintances, they hunted for weathered cottages dressed with Maine’s signature clapboard and cedar shingles.

The Maine House concept took shape organically, with the lens leading the way. “My husband (novelist Peter Behrens) kept saying we needed a ‘through line’,” Burwell said. “But Maura and I knew it would become clear if we just kept shooting. We always came back to the notion that we’d know it when we saw it… and we were right. Everything fell into place pretty naturally.”

The pair logged 3,000 miles—ferrying across bays and inlets, braving dirt roads in a borrowed French Citroen and combing seaside towns—going the extra mile, literally, for the sake of the shot. They woke at dawn to catch the misty sunrise light hovering over the harbor. They canoed out onto a lake in Camden during a summer heat wave (“I paddled while she took photos”) and bunked overnight on cots in a converted attic on Vinalhaven (“We climbed the ladder like we were at summer camp”). Each house they photographed steered them to two or three more.

“It was arduous at times, but well worth it,” Burwell said. “It took persistence, lots of hard work, great partners and a treasure-hunt approach.”

The images eventually settled neatly into chapters, threaded together seamlessly by Hackett’s prose to create what Décor Maine magazine calls “equal parts book, anthology and urgent call to action.”

“Here are the homes created by the people who live in them, distinctive for their ingenuity, originality and fierce individuality,” Hackett writes in the foreword. “Here are the spaces that personify the artists whose work is made better through struggle, a Mainer’s point of pride. Here are cottages resolutely unchanged—where to silence a slamming screen door would be to strip the place of its soul. Here are the warped floorboards and lovingly worn camp sofas sat on by generations of the same family. Here are the spaces where a life well-lived is defined by spirit, creativity and longevity. Here is a kind of visual wealth that money just can’t buy.”

“Berman, who is also an art conservator with a specialty in textiles, uses them to inject color into the guest bedroom.”

(From “Little Peek” chapter)

“A brick parquet floor and granite walls, warmed by the sun, fit seamlessly into the rugged Maine landscape.”

(From “High Head” chapter)

"Guests are treated to luxe camp-style quarters in the attic, where cots are fitted out with downy duvets and homespun linen.”

(From “A House Over the Shop” chapter)

Three women with roots in three different parts of Maine share the same goal: to preserve the swiftly vanishing Maine of their childhoods.

From Left to Right: Kathleen Hackett, Basha Burwell, Maura McEvoy

The Gentle Trespasser

Photographs in the book tell the homes’ stories without including their inhabitants—a decision the collaborators made early on in the project. The absence of people lends an aura of mystery, while preserving the homeowners’ anonymity. Naturally standoffish, Mainers cherish their privacy.

“I’m quite the opposite,” Burwell said with a laugh. “My friends say I have a certain resourceful scrappiness that allows me to get what I want. I call myself the gentle trespasser because I’ve gotten really good at walking up a driveway, respectfully and carefully, and introducing myself.”

Burwell credits her work with L.L.Bean with making the most out of these extroverted qualities. “I must have gone into 1,000 homes over those years,” she said. “It helped me hone my visual aesthetic and what I’m drawn to, but also taught me to be daring and introduced me to so many people up and down the coast of Maine.”

‘You’re Maine’

Maine—and L.L.Bean—are in Burwell’s blood. Her ancestors were Boothbay schooner captains, and her great grandfather, William Harden Foster, was the first artist to grace the cover of an L.L.Bean catalog in 1925 with his painting, The Moose Hunter.

“He knew Leon (L.L.) and, legend has it, they duck hunted together in South Freeport,” Burwell shared.

Both of Burwell’s parents were born in South Freeport, the tiny village bordering Bean’s hometown. She learned the beauty and value of preservation from her father, who renovated their homes with his own hands and instilled in her a passion for special Maine houses. As a kid, she bounced between one grandmother’s grand colonial house and the other’s 1911 cottage overlooking Harraseeket Harbor.

Every Christmas, one of her grandmothers ordered her 17 grandchildren matching items from the L.L.Bean catalog. “My cousins and I would unwrap the same sweater or pair of slippers,” she recalls. “To this day, I still wear a ton of Bean gear.”

Burwell's family cottage in South Freeport, circa 1911. Photo courtesy of Foster family and Basha Burwell.

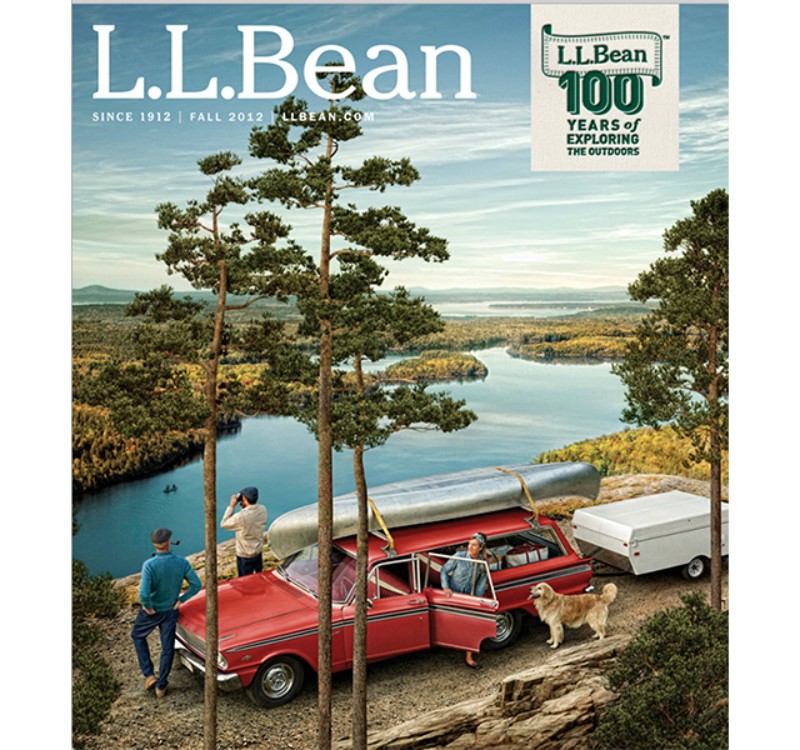

Burwell on the 100th Anniversary L.L.Bean Catalog cover.

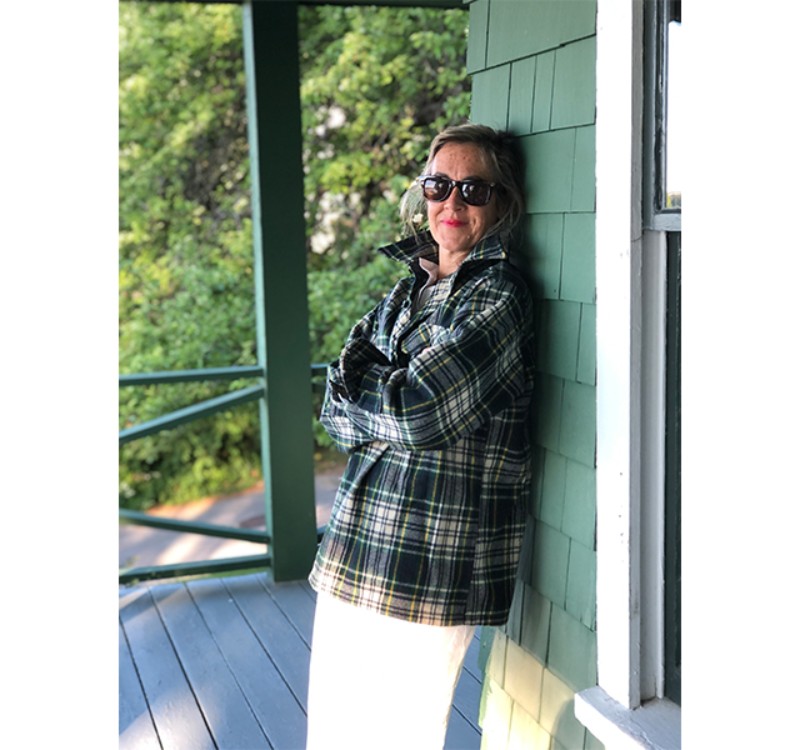

Basha on her family's shared South Freeport cottage porch, favorite vintage L.L.Bean wool jacket.Photo courtesy of Basha Burwell.

Speaking of the Bean catalog, she swiveled to the other side of the camera in 2012 for a 100th anniversary shoot. “They brought in photographer Randall Ford from Austin to recreate a series of classic covers, and I was hired as a model,” she said. “I got to sit in the makeup chair and ride in a golf cart versus lugging props around. It was a bit of a full-circle experience.”

When McEvoy, who has spent every summer of her life on the Maine coast, began exploring the idea for The Maine House in 2018, she immediately thought of Burwell. The pair had worked together at Garnet Hill and remained friends and collaborators.

“‘I want to do a book about Maine and immediately thought of you because you’re Maine,’” Burwell recalls McEvoy telling her over the phone from the road.

The three authors’ goal with the book is to tell the story of the Maine that has made an indelible imprint on the lives of so many—an enchanting and now endangered vision.

“Our hope,” Burwell concluded, “is that The Maine House serves as both a record of and a tribute to the place we all want it to be.”